Slate, February 3, 2017

This essay puts contemporary anti-immigrant politics in historical perspective by narrating clashes between rival ideas of the United States and its relationship to immigration: an asylum ideal which held that the United States, as a republic, must offer refuge to the oppressed of all nations, and competing visions of a besieged America in need of racial and ideological protection. The claim that xenophobia is “not who we are” won’t withstand historical scrutiny, but there are also imperfect, countervailing traditions based on welcome, generosity and connection worth revisiting.

The Statue of Liberty’s long career as a beacon to the oppressed began in 1882 with refugees whose religion some Americans feared. The czar was cracking down on Jews, and tens of thousands of people fled across Europe, many reaching the East Coast of the United States. Jewish American organizations rushed to aid them, as commentators debated what the sudden influx meant. What, if anything, did America owe these impoverished strangers, with their non-Christian faith? In a booming industrial society hungry for workers but fearful of beggars and bomb-throwers, were they a benefit or a danger?

It was at this moment that a Jewish American poet in New York, Emma Lazarus, made her way to the depot on Wards Island, where the refugees were being housed. Moved by their suffering, she taught classes and pressed for better shelter, food, and sanitation. Later, Lazarus was asked to contribute a poem for an auction to raise funds for the Statue of Liberty’s pedestal, and here she did something strange.

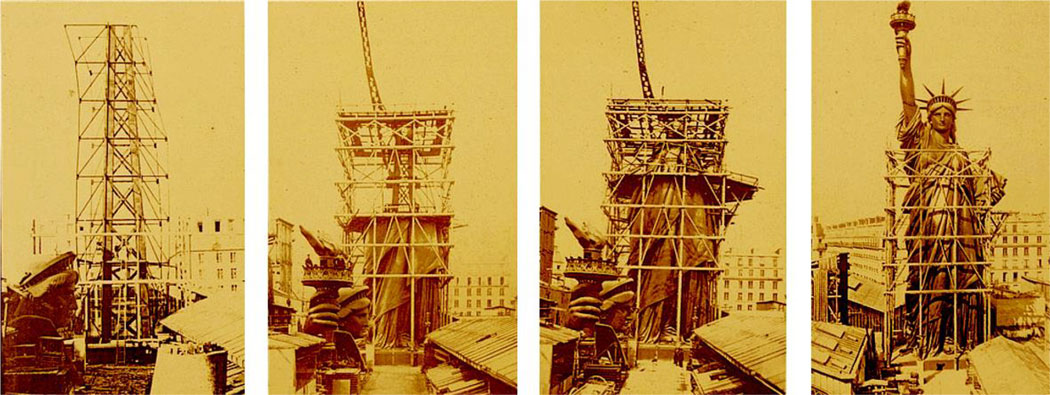

Until then, the icon had symbolized Franco-American friendship and trans-Atlantic republicanism. But in her sonnet, Lazarus recast it as a welcome signal to the poor and threatened, a “Mother of Exiles” calling out to the world to give over its “huddled masses yearning to breathe free.” Lazarus’ statue was not asking: “Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost, to me”; it commanded. The poem wore its ambivalence about immigrants on its sleeve—“wretched refuse,” it called them—but it also expressed the idea of the United States as a haven for outcasts in bold new ways, ways that would face repeated onslaughts in the coming decades.

Last week, Donald Trump launched the latest of these attacks, issuing an executive order that suspends the entrance of all refugees for 120 days, prohibits the entry of citizens from seven Muslim-majority countries for at least 90 days, and bars Syrian refugees indefinitely. Given the racist, anti-immigrant nationalism at the center of Trump’s presidential campaign, his action came as no surprise. For his supporters, it represented a blow against menacing Islam and an assertion of white, Protestant identity as the genuine core of what it means to be American. For Trump’s many critics, it represented an outrageous affront to the United States’ deepest values as a beckoning “nation of immigrants,” the tradition that Lazarus championed.

Both stories about immigration and America—that there was a glorious past in which America was pure and protected from outsiders, or that Americans have always prized multicultural inclusion—remake the past to score political points in the present. In fact, Trump’s vile exercise in nativism—the xenophobic celebration of the national self—is only the latest maneuver in a series of battles over immigrants’ role in American life and America’s place in the world. Viewed historically, the claim that these anti-immigrant policies are “not who we are,” while stirring, does not hold water. American nativist politics have deep roots.

The founders made clear enough who among immigrants they envisioned to be potential citizens, barring naturalization to all but “free white persons” who had been in the country two years. In the mid-19th century, America’s first mass nativist movement directed Protestant nationalist fury against Irish Catholic immigrants suspected of depravity and papal allegiances that would corrupt the United States’ free institutions. In the 1880s, anti-Chinese movements, fired by fears of labor competition and civilizational decline, won the first congressional legislation restricting immigrants on the basis of racialized national origin. Hatred of immigrants as poor and working people—assumed to be lazy, immoral, and given to “dependency” on American largesse—animated U.S. nativism from its birth.

But also from the beginning, anti-immigrant forces had to contend with countervailing traditions. Nineteenth-century Americans took very seriously the notion that the United States—an emerging republic in a world of powerful monarchies—had a duty to offer safety to those escaping political repression elsewhere. If the United States wanted the distinction of being an exemplary and exceptional republic, Americans must hold open their doors for the persecuted.

According to this ideal, refugees fighting for their homelands’ freedom could keep their torches alight in America, mobilizing fellow exiles, financial resources, and public opinion to advance their causes worldwide; Americans would promote the global advance of liberty precisely by serving as a welcoming harbor for the persecuted. “All are willing and desirous, of course, [that] America should continue to be a safe asylum for the oppressed of all nations,” Daniel Webster put it in 1844.

There were, to be sure, stark limits on the asylum ideal and its influence. The sense of who deserved political shelter was mostly reserved for Europeans; Asians need not apply. (Even Webster, in his remarks, hailed America as an asylum just before calling for limitations on immigrant voting.) By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, when the American industrial order was challenged by militant labor, socialist, and anarchist movements often led by immigrants, policymaking and intellectual elites clamped down, approaching freedom-seeking immigrants not as transnational partners in liberty, but as sources of disorder, revolt, and danger. As American society was transformed by the arrival of millions of Southern and Eastern Europeans, a new and authoritative racial science confidently consigned newcomers to the lower tiers of humanity, a eugenic menace to be contained and excluded.

But the asylum ideal held on stubbornly, less among native-born Americans than among immigrants themselves and their descendants, who made it their own. More than anyone else, it was immigrant and immigrant-descended intellectuals—Lazarus and her spiritual offspring—who rebuilt the Statue of Liberty into a sign of greeting and protection.

The tides were against them. As the United States emerged as a world power—seizing colonies, waging war in Europe, engaging in great power diplomacy—perceptions of national interest subordinated humanitarian concerns. Having achieved only limited gains in their first half-century of campaigning, anti-immigrant forces triumphed in the wake of World War I, as moral panics over possible German immigrant subversion spilled over into terror at European immigrants generally, especially as underground Bolshevik agitators.

Beginning during the war and culminating in 1924, the United States slammed its door on most of the world: excluding nearly all immigrants from Asia and stringently restricting European immigrants on the basis of “national origins” quotas aimed at turning fantasies of an earlier America that was Northern and Western European and Protestant—not Italian, Jewish, and Slav—into demographic realities. As prominent race theorist Madison Grant warned in 1916, the new immigration had brought “a large and increasing number of the weak, the broken and the mentally crippled of all races”; Americans must abandon the “pathetic and fatuous belief in the efficacy of American institutions and environment to reverse or obliterate immemorial hereditary tendencies.” Grant and his associates trumpeted exclusion in unapologetically nationalist and racist terms: The United States must preserve and strengthen its heritage by barricading itself off from invasions and influences from lesser parts of the Earth.

Between the 1920s to the mid-1960s, questions of racial self-preservation, labor protectionism, and national interest largely framed American immigration politics. These were the United States’ first Trumpian decades in immigration terms. Restrictionists refashioned the Statue of Liberty into a militant warrior-goddess guarding America’s beleaguered gates. New anti-radical policies kept out and aided the deportation of actual, and imagined, activists on the left. Jewish escapees from Nazi Germany were refused on the grounds that they were likely to become “public charges.” Tens of thousands of people of Japanese descent—immigrant and citizen alike—were imprisoned on the basis of racially presumed disloyalty. Nothing raised the walls of fortress America faster than wars, real and metaphorical: They stoked anxieties about keeping hostiles out and locating secret adversaries within, turning neighbors into enemies.

Advocates for immigrants found themselves on the defensive, compelled to argue, more intensely than ever, that immigration served U.S. national goals. Previously, a case could be made that freedom-loving, imperiled immigrants deserved shelter; now immigrants had to prove they were obedient, conservative, assimilating, and willing to die for the nation.

In the decades after World War II, the United States’ exclusionary controls came under new pressures and eventually buckled. Immigrant groups, having fought their way into both the middle class and citizenship rights, lobbied for openings that would allow their relatives’ entry and lift racial stigmas.

Some of the most effective anti-restriction arguments were those of Cold War strategy. As the United States sought to project its power globally, contain communism, and encourage the Third World’s allegiance, exclusion was seen more and more as a problem rather than a solution. Anti-communists from Eastern Europe and Asia who were trying to escape to the United States were running into hard legal barriers. Even as the U.S. sought to attract trained foreign experts to build up its military technologies, restrictive laws were keeping them out. And there was the problem of messaging. If you wanted the people of Africa, Asia, and the Middle East to believe American promises to responsibly lead the “free world,” racist immigration controls were not helpful; American Cold War propagandists worried about the rich material that “national origins” quotas provided Soviet propaganda mills.

Confronted from many sides, the national origins quota system gave way and was replaced by the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, which prioritized family reunification, technical expertise, and selected refugee admission (even as new restrictions were placed on Western Hemisphere immigration). “No person shall receive any preference or priority or be discriminated against in the issuance of an immigrant visa because of his race, sex, nationality, place of birth, or place of residence,” it stated.

After the passage of the 1965 act, the United States witnessed the arrival of immigrants from Asia, Latin America, and Africa. This was an unintended consequence; the law’s architects had promised that its nondiscriminatory terms would not alter American demographics in practice, even as they sent the right signals. Arriving in the wake of the black freedom struggle, post-1965 immigrants insisted on a more expansive, democratic definition of America itself, pushing forward the long work of untethering American national identity from presumptions of conformity, homogeneity, and political consensus.

It was during the Cold War years that the meanings of refuge emerged as one of the most contested battlegrounds of immigration politics. As the United States government bolstered authoritarian states with military and economic aid, sponsored proxy wars, and sent its own troops to suppress regimes it disliked, violence deployed by the U.S. itself generated vast numbers of dislocated people, some of whom found their way to American borders. Geopolitical double-standards were built into U.S. immigration law: Those fleeing communist regimes (like Cuba) were more likely to be permitted entry as political refugees, while those escaping dictatorial U.S. allies (like Haiti) were often rejected as “economic migrants.” Many of those turned away suffered cruelty or death at the hands of brutal states.

With great effort, activists managed to redefine refugee status in U.S. policy along more international lines. The definition of a refugee that the U.N. had adopted in 1951—someone with “a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion” in his or her home society—were finally integrated into U.S. law in 1980. Although refugee advocates still had to fight to guarantee fair enforcement, Emma Lazarus would have smiled.

But early in the 21st century, refugees, and immigrants generally, proved vulnerable to targeting by demagogues, as American policymakers pursued unbounded wars in the Middle East, companies based in the United States moved their plants abroad in search of lower-paid workforces in less democratic states, and scapegoats were sought for an economic crisis wrought by predatory elites. Unwilling to address the inequalities upon which their own interests depended, reactionary politicians sharpened and exploited dividing lines between insider and outsider.

This is the vein that Trump cunningly mined in pursuit of power. It is one that the Protestant haters of Irish Catholic domestics, white fighters against Chinese railroad workers, eugenicist race-counters, and the deporters of supposed communists would easily recognize and uphold. Like it or not, Trump’s aggressive, racist nativism is not a deviation from American history but flows from some of its oldest, strongest currents. But it is also worth revisiting the refuge tradition Emma Lazarus put to paper, though not as an exceptionalist virtue (other societies welcome refugees) or a perfect ideal (remember the “wretched refuse”) or, as during the Cold War, a foreign policy instrument.

What if Americans set themselves to widening their limited but meaningful history as a country of refuge: their sense of whose life counted, the kinds of hardship that mattered, and their obligations to a world from which their wealth and power cannot be separated? Visions of a generous United States, of America as a shelter for the oppressed, have beaten back formidable exclusionary forces in the past, and may yet again.