This historiographic essay discusses, promotes and critiques “new histories of American capitalism,” arguing for the benefits of reframing this enterprise methodologically, as political-economic history, and making the case for the necessity and multiple, reciprocal benefits of connecting histories of capitalism to histories of the United States in the world. It then presents ongoing research by historians of the US in the world that deals with political-economic themes, including scholarship on commodities, consumption, law, debt, militarization, migration, labor, race and knowledge regimes.

The Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era (2016)

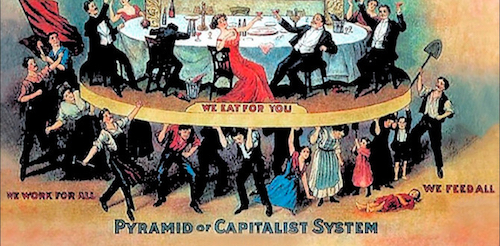

One of the chief promises of the emerging history of capitalism is its capacity to problematize and historicize relationships between economic inequality and capital’s social, political, and ecological domain. At their best, the new works creatively integrate multiple historiographic approaches. Scholars are bringing the insights of social and cultural history to business history’s traditional actors and topics, providing thick descriptions of the complex social worlds of firms, investors, and bankers, while resisting rationalist, functionalist, and economistic analyses. They are also proceeding from the assumption that capitalism is not reducible to the people that historians have typically designated as capitalists. As they’ve shown, the fact that slaves, women, sharecroppers, clerks, and industrial laborers were, to different degrees, denied power in the building of American capitalism did not mean that they were absent from its web, or that their actions did not decisively shape its particular contours.1

In broad terms, the work’s enabling concept has been embeddedness. Where both conventional business and Marxist historical approaches gave primacy to capitalists’ autonomous actions in pursuit of their interests, historians have enlisted Karl Polanyi to situate these figures, their activities, and capitalist power relations generally within conditioning structures of law, policies and institutions, social norms, practices, and resources.2 This has helped give American capitalism a more thoroughly historical politics, against the formidable teleological engines typically activated to account for change. As much as Polanyi, these scholars’ necessary partners have been the new political and legal historians, who, informed by the social sciences, have a supple sense of the ways that institutionalized power shapes political contests and outcomes.3 If, for Marx, the bourgeois state was capital’s boardroom, these historians have demonstrated that different sectors of capital demanded varied and often incompatible actions from government, and that state institutions, rather than simply conforming to these pressures, had structuring power of their own. Marx’s boardroom has been rendered more crowded, conflicted, and contingent, exercising a more variable range of powers than imagined.4

Also critical to the field’s interpretive success has been its willingness to address capitalism’s spectrum of discipline, coercion, and violence. To the extent that capitalism is being denaturalized, it raises the question of how its ongoing expansion has been politically achieved. Legitimacy and compliance explain only so much: requiring attention to force. In turning to these questions, historians have challenged venerable, liberal presumptions about the system’s voluntarist character, contractual modes, and technorational operations. They have also contested liberal and Marxist understandings of capitalism’s definitional reliance on “free” labor, allowing them to better chart struggles over the terms of exploitation and freedom, and to listen in more keenly to historical actors’ arguments over these themes.

Degrees of unfreedom were, of course, not a new theme to historical scholarship; they had been a focal point of labor historians’ accounts of workers’ struggles, and foundational to the historiography of slavery. But the study of coercion under the “history of capitalism” rubric suggested that coercive power was systemic: war, enslavement, dispossession, eviction, enclosure, incarceration, blacklisting, strikebreaking, and the police and military suppression of labor appeared as unexceptional instruments for imposing, securing, and extending regimes of commodification, both during and beyond moments of “primitive accumulation.” The centrality of coercion to American capitalism, and the Atlantic and global labor systems from which it was inseparable, has been most rigorously explored in the burgeoning study of slavery as a mode of capitalist production and labor organization. Drawing on insights from colonial and postcolonial intellectuals, this scholarship has dramatically countered prevailing assumptions about slavery’s status as “in but not of” capitalist modernity, recasting it as laboratory, engine, and financial bulwark. As a result, the lash has now assumed its proper place alongside the stopwatch in capital’s arsenal.5

Despite the field’s accomplishments and potential, the “new history of capitalism” faced and faces a number of challenges. First, there was wariness about defining the axial term “capitalism” itself, an evasion sometimes defended as a virtue.6 Did capitalism denote a feature of society, or a social totality in which all features were more or less subordinated to the projects of commodification and accumulation? Or was it just a project or activity, something that capitalists (however you defined them) did? To what extent was the study of capitalism coterminous with studies of the “material” or the “economic?” What place (if any) did systems of meaning-making, the defining subject of cultural history, play in capitalism’s trajectory? In more directly political terms, was the problem the scope, character, and power of capital in a particular setting and moment, or its existence as a sociopolitical force at all?7 The issue here was not that historians disagreed on their answers to these questions. It was, rather, the extent to which they proceeded from unstated, know-it-when-you-see-it presumptions, or dismissed definitional debate itself. In such cases, “capitalism” could appear more of an advertisement than a tool for opening historical inquiry.

There was the way that prominent historians of capitalism defined their project against “culture,” often erroneously conflated with the study of race, gender and sexuality. This move sometimes came with a revanchist edge: after decades exiled to the wilderness by cultural historians, the materialist motors of historical change—especially state formation and capital accumulation—were retaking history’s commanding heights, and frivolous superstructures were being consigned to their proper place. To be sure, some of the scholarship targeted in this way had advanced what might be called a disembedded approach to culture, race, gender and sexuality, conflating power with representation, abstracting patterns of meaning from the material forces and institutional structures to which they were tied, and paying relative inattention to economic inequality. But such historiographic framings, rather than confronting and overthrowing age-old 332 Paul A. Kramer dichotomies—material/ideational, base/superstructure, class politics/identity politics— doubled down on them. Some historians of capitalism managed to steer their crafts creatively through these roiling waters, reconstructing capitalism’s cultures and the intimate entanglements of economic exploitation and racialized, gendered and sexualized power and difference. But others embraced the satisfactions of a self-vindicated government-inexile returning to power, dispelling vanquished methods and analytics to the margins.

Relatedly, there was the hype. The “new history of capitalism” label proved an effective brand: while some scholars acknowledged their indebtedness to business, economic, and labor history, the term suggested temporal and interpretive distance from these fields. It managed to insulate itself—perhaps better put, to disembed itself—from explicitly political questions, allowing the “history of capitalism” to gather together undergraduate enrollees, audiences, and scholars that embraced capitalist power relations and sought managerial, how-to answers, as well as those that brought critical perspectives to bear. There was also highly successful marketing, with spokespeople celebrating the field’s bold innovation and unique ability to speak to the present crisis in presentist terms. This amounted, not without irony, to something like historiographic capitalism: the pursuit of resources, prestige, and position through declarations of novelty and obsolescence. Next year’s shiny models were already on the showroom floor: did you really want to be caught driving around last year’s?8 Academic hype comes in many flavors, but it inevitably courts backlash, as self-conscious outsiders (and even some insiders) push back. When critics target a new field’s exaggerated self-promotion, its genuinely substantive insights can get lost in the melee. The questions raised by the new historiography of capitalism are simply too important for them to be rendered vulnerable to, or confused with, the boosterism that attended its birth.

What is at stake in all this, not merely for historians, but for the larger societies in which they are embedded? By following capital’s imperial trajectories both within and across national boundaries, historians of U.S. capitalism will enable themselves to do the necessary work of grounding capital’s history in human agency and political struggle, against the culturally dominant tendency to tell its story in naturalizing, teleological, or instructional modes. Among the most generative sites of investigation will be social locations where scholars can chart the expansionary forces of capital as they confront the demos, the commons, and the web of life. It is precisely in such contests, in which the agents of commodification meet their political, social, and ecological antagonists, that capitalism’s intricate, disputed operations may emerge most sharply, as its self-justifying mythologies battle, break down, and steel themselves against the challenges of politics and history. In other words, the projects of subjecting capitalist forces to critical, historical analysis, and of organizing material and economic life to serve the goals of collective well-being, democratic power, and ecological sustainability, are intimately tied.