This essay discusses ongoing challenges in the historiography of U. S. colonialism, through a critique of Daniel Immerwahr’s 2016 article in Diplomatic History, “The Greater United States.” It discusses the ways Immerwahr’s article draws upon a number of widespread problems in this field: a terminological conflation of U. S. colonialism with “empire” generally; the collapsing together of different sovereignty relationships; the use of actors’ categories for analytical purposes; and the minimization of a vast, existing scholarship as insufficiently “mainstream.” Identifying these problems, it is hoped, will help a flourishing scholarship advance; the piece ends with an extensive bibliography of dissertations and published monographs in the field completed since 2007.

Historical scholarship on U.S. overseas colonialism in the twentieth century, a crucial subset of a broader literature on U.S. empire, has blossomed with unprecedented vitality over the past two decades. Working on U.S. colonial rule and military occupation in the Philippines, Hawai‘i, Guam, Samoa, Puerto Rico, the Panama Canal, Haiti, the Virgin Islands, and other locations under military-colonial control, from positions in U.S. history, American Studies, Southeast Asian history, Pacific history, and Caribbean history, scholars have produced a stunning variety of works that have complicated familiar narratives, uncovered the voices of previously silenced agents, excavated neglected events and processes, altered conventional timelines, and brought new analytic categories to bear on studied and unstudied pasts. Thanks to this scholarship, historians know more than ever about colonialism’s complex impacts on the lands and people that came under U.S. control, the specific operations of a diverse array of colonial regimes, as well as and the many and conflicting roles played by colonized subjects in shaping U.S. impositions (resisting and delimiting, facilitating and enabling, initiating and enacting). Their research is wide-ranging, covering: the dialectical relationships between asymmetrical sovereignties and exceptionalizing ideologies of race, religion, gender, and sexuality; colonialism’s politicaleconomic operations, from modes of commodity production to regimes of labor discipline to systems of financial control; Americans’ ideological, institutional, and material exchanges with other colonial regimes; the deep legacies of Spanish colonial history in shaping U.S. colonialism’s outlooks, patterns, and institutional structures; and the limits of U.S. colonial power as it confronted popular and elite resistance, institutional dysfunction, environmental obstacles, and inter-imperial challenges.

They have also advanced the project of unraveling the formidable, counterproductive distinction between “formal” and “informal” empire by revealing both the spectrum of sovereignties that lay between “dependency” and “independence” in U.S. imperial practice, and the profound reliance of U.S. commercial expansion and military projection—the usual stuff of “informal empire”—upon U.S. overseas colonies, as infrastructural and commercial anchors, military platforms, and institutional and ideological laboratories. Finally, these scholars have seriously challenged the spatial frames with which many U.S. historians have confined overseas colonialism to a distant, fleeting (and sometimes forgettable) “out there,” revealing the myriad ways that U.S. colonial empire came “home” to the metropolitan United States in the form of migrating colonial subjects, circulating commodities, refluxing innovations, and new, colonizing modes of nationalist, racialized, and gendered ideology. Without subordinating these histories to the requirements of U.S. national history, they have transformed the historiography of the United States in the world by insisting on and demonstrating the centrality of U.S. colonialism to twentieth-century U.S. history generally.1

This scholarship’s depth, richness, and sophistication make the field Daniel Immerwahr depicts in his 2016 essay “The Greater United States,” difficult to recognize.2 Adapted from his SHAFR Bernath Lecture Prize address and published in Diplomatic History, the piece is an odd summons which calls upon U.S. historians to pay attention—finally—to what the author depicts as the stillneglected history of U.S. overseas colonies. Immerwahr’s essay is worth highlighting as an example of modes of thinking about U.S. empire that, despite many breakthroughs, stubbornly persistent.

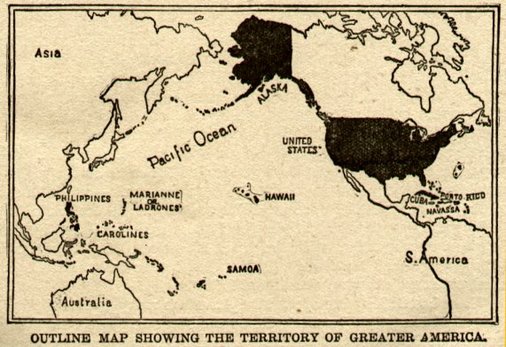

The article’s main lines of argument are as follows. The United States’ post-1898 “formal” colonies have not been adequately studied by U.S. historians writing in “mainstream” settings, while historians of U.S. empire have long over-emphasized “informal empire” at the expense the United States’ “formal” empire. These territories and the people who lived there ought to be viewed as part of the “domestic” history of the United States. In framing the colonies this way, historians should follow the lead of early twentiethcentury Americans, some of whom viewed them as part of a cartographic imaginary of “Greater America.” Approaching post-1898 history in this manner reframes nineteenth-century continental expansion as part of a longer, more global history of irregular “territory.” The United States’ overseas “territories” should be seen as significant, to historians and others, because if one adds up all the populations governed by the United States in the midtwentieth century—not only the island colonies, but military bases and postWorld War II occupation zones—they are impressive when compared to both other modern global empires and U.S. “domestic” society as conventionally understood. While the “Greater United States” experienced a striking expansion during and immediately after World War II, equally striking was the United States’ “unprecedented” shedding of territory immediately afterwards. Embarking on the study of the “Greater United States” will enable historians to move beyond the traditional, schoolhouse “logo map” that conventionally defines the nation.

Every one of these arguments is problematic, but the article is nonetheless instructive: in just under twenty pages, it condenses, repackages, and celebrates nearly all the major flawed assumptions that have compromised the historiography of U.S. overseas colonialism since its beginnings, even as it brands this perspective a bold, original, forward-looking conception of U.S. imperial historiography. Strangely, the essay’s principle interpretive moves are precisely those which the best of the last decade’s scholarship have rejected. But there may be something here for historians: a conversational, easy-to-digest model of exactly how they should not write histories of U.S. overseas colonies, U.S. empire, or the United States in the world.

In what follows, I will discuss the main problems with this piece and others, with an eye towards what historians might take away. Much of the critique that follows may be obvious to the many scholars doing innovative work on the history of the United States in the world. But the effort is worth making, among other reasons, because Immerwahr’s article reflects problematic assumptions that have a long history and remain in wide circulation. What follows, then, is offered in the hope that a discussion of this essay’s shortcomings, common to many past and present-day histories of U.S. empire, might shed light on questionable, long-standing, and prevalent historical practices and, through this critique, point towards more generative modes of inquiry.

The first problem is the conflation of U.S. colonialism with “empire.” Here Immerwahr’s essay rides a wave of faulty nomenclature and periodization that began with the opponents of U.S. overseas colonialism in the wake of 1898. For many early twentieth-century critics of U.S. overseas colonialism—the selfdescribed “anti-imperialists”—the conquest and annexation of overseas colonies represented a great, tragic break-point, the time and place where an American “empire” began. Built to gather the movement’s multitudes—liberal Republicans, white supremacist Democrats, labor activists, Northern intellectuals—around a racialized, nationalist jeremiad, this definition of empire as limited to overseas territorial annexation was and is notable for its strategic narrowness. It wrote off indigenous dispossession, the Mexican-American War, territorial annexation in North America, gunboat diplomacy in East Asia and Latin America, and navalist competition, for example. “Imperialism” cast the post-1898 colonialist surge as a reversible lapse, an exception that proved the rule of peaceful, commercialist, republican expansion across and beyond North American space.

Rhetorically and conceptually, this reduction of U.S. empire to post-1898 overseas colonialism proved a generous gift to those seeking to legitimate and depoliticize most expressions of American global power in the twentieth century. “Empire” was just a chapter in the textbook, a fleeting “moment” in U.S. history amid other moments. Shrinking U.S. empire to an island in history was helped along by the fact that post-1898 U.S. colonialism involved actual islands.

Despite the intensifying, asymmetrical impacts of U.S. metropole and colony on each other, and the structural necessity of overseas colonies to other projects of U.S. global power, the post-1898 U.S. colonies were and are separated off, the historical and ethical partitions built from oceans.3

There were, importantly, formidable efforts to challenge apologetic definitions of empire. During the interwar period, pacifist, socialist, feminist, and Christian opponents of U.S. great-power politics, arms build-ups, and military colonial interventionism in the Caribbean enlisted idioms of empire to make critical sense of a far broader swath of American foreign relations than the late victorian critics, and often did so in distinctly structuralist, anti-nationalist, and anti-exceptionalist ways.4 Later, the Wisconsin School reframed U.S. history around a concept of “informal empire” that, while rigid and in some ways exceptionalist, gained critical and analytical power among other things from its decisive break with early twentieth-century framings.5

Nevertheless, as the result of self-conscious politics and terminological inertia, “empire” and “imperialism” continued to cleave tightest to U.S. histories involving the Philippines, Puerto Rico, Hawai‘i, Guam, Samoa, the Virgin Islands, and the Panama Canal Zone. Permitted relatively free rein in this terrain, “empire” remains contested elsewhere. Indeed, to a significant degree, the uncomplicated presence of “empire” in discussions of the post-1898 U.S. colonies helped produce its necessary absence elsewhere. (To be sure, this kind of selective outrage is also a common feature of other historiographies: the especially brutal, scandalized colonialism that normalizes the other, quieter ones; the flagrantly exploitative capitalist who draws indignation away from more prosaic systems of exploitation, etc.)

This narrow definition of “empire” as territorial control is extremely common among influential historians working in a number of fields, and writing over many decades. On some occasions, this definition is presented openly, as when Ernest May wrote in 1968, on the origins of post-1898 colonialism, that his book “deals with imperialism narrowly defined as direct territorial acquisition….”6 In other cases, the definition is implicit in the kinds of intervention that are included and excluded from the category. In a 2009 essay that argues against the applicability of “empire” to nearly all aspects of U.S. foreign policy, Jeremi Suri makes an exception for the post-1898 colonies. “Beyond this band of islands in the Caribbean and Pacific where Washington acted as a colonial power,” he writes, “the term empire cannot capture the complexities of American influence in a wider global arena encompassing China, Europe, and the Middle East, as well as other regions.”7 In a recent, monumental interpretation of U.S. empire, A. G. Hopkins writes that “the United States … had an empire between 1898 and 1959,” its “insular empire,” but that after 1945, it “ceased to be an empire” and was, rather, a “world power without having territorial possessions.”8